Why are law school graduates still failing the bar exam at a high rate?

The first decline took place in the July 2014 bar exam, which some believed might be blamed on an ExamSoft software glitch. Then came continued declines in the July 2015 exam, which some blamed on the addition of Civil Procedure to the Multistate Bar Exam. The declines persisted and even worsened.

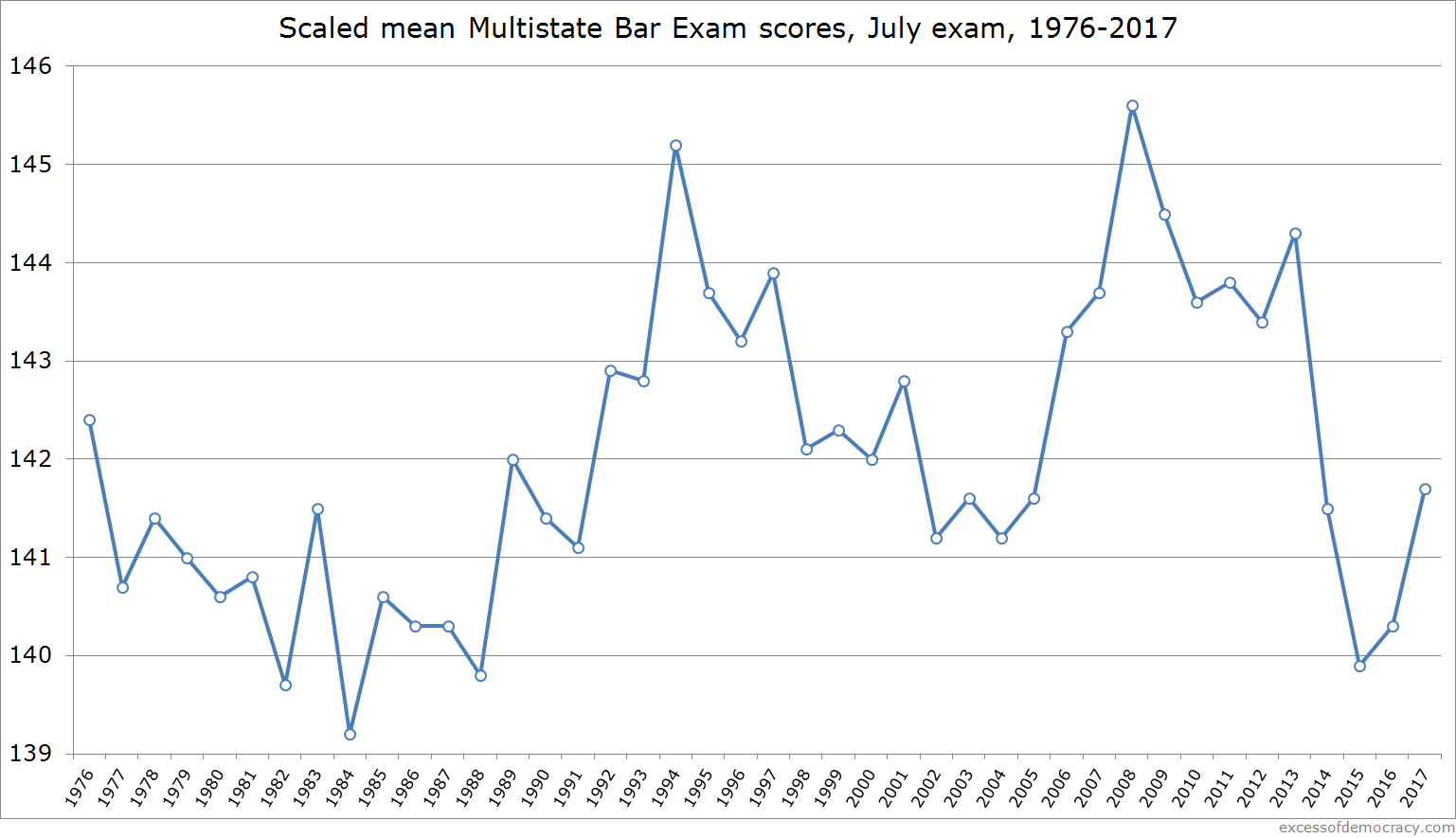

Five straight July bar exam cycles with persistent low pass rates across the country. But the bar exam has not become more difficult. Why?

One reason rates remain low is that predictors for incoming classes remain low. LSAT scores actually declined among the most at-risk students between the incoming classes admitted in the 2011-2012 cycle (graduating in 2015) and the 2014-2015 cycle (graduating in 2018). The 25th percentile median LSAT among full-time entrants dropped 2 LSAT points between those who graduated in the Class of 2015 and the Class of 2018. Indeed, 11 schools saw a drop of at least 5 LSAT points in their 25th percentile incoming classes—almost as many as those that saw any improvement whatsoever (just 12 schools, including Yale and Stanford).

Not all LSAT declines are created equal: a drop from 170 to 168 is much more marginal than a drop from 152 to 150; and a drop can have a bigger impact depending on the cut score of the bar exam in each jurisdiction. But it’s no surprise, then, to see the persistently low, and even declining, bar passage rates around the country with this quick aggregate analysis.

Nevertheless, since around September 2014, law schools have been acutely aware of the problem of declining bar passage rates. Perhaps it was too late to course-correct on admissions cycles through at least the Class of 2017.

But what about academic advising? What about providing bar preparation services for at-risk students? Given that law schools have been on notice for nearly five years, why haven’t bar passage rates improved?

I confess, I don’t know what’s happened. But I have a few ideas that I think are worth exploring.

First, it seems increasingly likely that academic dismissal rates, while rising slightly over several years, have not kept pace to account for the significant decline in quality of entering students. Of course, academic dismissals are only one part of the picture, and a controversial topic at that, particularly if tethered to projections about future likelihood to pass the bar exam on the first attempt. I won’t delve into those challenging discussions; I simply note them here.

Another is that law schools haven’t provided those academic advising or bar preparation services to students—but that seems unlikely.

Still another, and perhaps much more alarming, concern is that those bar services have been ineffective (or not as effective as one might hope). And this is a moment of reckoning for law schools.

Assuredly, when the first downturns of scores came, law schools felt they had to do something, anything, to right the ship. That meant taking steps that would calm the fears of law students and appease universities. Creating or expanding bar preparation courses, or hiring individuals dedicated with bar preparation, would be easy solutions—law students could participate in direct and tangible courses that were specifically designed to help them achieve bar exam success; law faculty could feel relieved that steps were being taken to help students; university administrators could feel confident that something was being done. Whether these bolstered existing courses or added to them, assuredly schools provided opportunities to their students.

But… to what end? Something was done at many institutions. Has it been effective?

Apparently not. The lagging (and falling) bar passage rates are a sign of that. Granted, perhaps the slide would be worse without such courses, but that seems like cold comfort to schools that have been trying to affirmatively improve rates.

We now have the first evidence to that effect. A report commissioned by the California State Bar recently studied several California law schools that disclosed student-specific data on a wide range of fronts—not just LSAT and UGPA in relation to their bar exam score, but law school GPA, courses taken, even participation in externships and clinic.

One variable to consider was involvement in a bar preparation course. Did participation in a bar preparation course help students pass the bar? I excerpt the unsettling finding here:

Five law schools provided data for this variable. Students averaged about 1.5 units (range 0 to 6). For all those students, there was a -.20 (p<.0001) correlation between the number of units taken and CBX TOTSCL [California Bar Exam Total Scale Scores]. The source of this negative relationship appears to be the fact that in five out of six [sic] of the schools, it was students with lower GPAs who took these classes. After controlling for GPA, the number of bar preparation course units a student takes had no relationship to their performance on the CBX. A follow up analysis, examining just the students in the lower half of GPA distribution, showed that there was no statistically significant difference in CBX TOTSCL for those who took a bar preparation course versus those who did not (p=.24). Analyses conducted within each of the five schools yielded similar findings.

This should be a red flag for law schools seeking to provide bar preparation services to their students. In this student, whatever law schools are doing to help their students pass the bar has no discernible impact on students’ actual bar exam scores.

Granted, these are just five California law schools and the California bar. And there has been other school-specific programs at some institutions that may provide a better model.

But it’s worth law schools considering whether students are on a path toward improving bar passage success or simply on a hamster wheel of doing more work without any discernible positive impact. More studies and evidence are of course in order. But the results from the last several years, confirmed by the study of five California law schools, suggests that revisiting the existing the model is of some urgency.