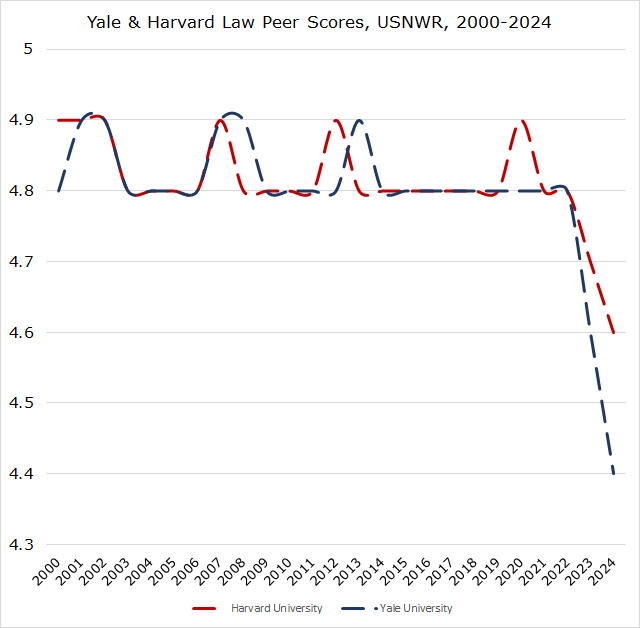

Yale, Harvard Law peer scores in USNWR law rankings plunge to lowest scores on record

Last year, I noted a change in the USNWR “peer score” for Yale and Harvard. Until this year, the “peer score” was the single most heavily-weighted component of the law school rankings. USNWR surveys about 800 law faculty (the law dean, the associate dean for academics, the chair of faculty appointments and the most recently-tenured faculty member at each law school). Respondents are asked to evaluate schools on a scale from marginal (1) to outstanding (5). There’s usually a pretty high response rate—last year, it was 69%; this year, it was 64.5%.

Until last year, Yale & Harvard had always been either a 4.8 or 4.9 on a 5-point scale in every survey since 1998.

Last year, Harvard’s peer score dropped to 4.7 Yale’s dropped to 4.6.

USNWR changed its methodology and reduced the peer score from 25% of the rankings to 12.5% of the rankings. It also explained, “Peer assessment ratings were only used when submitted by law schools that also submitted their statistical surveys. This means the schools that declined to provide statistical information to U.S. News and its readers had their academic peer ratings programmatically discarded before any computations were made.”

Harvard’s score dropped again to 4.6. Yale’s score plunged again this year, to 4.4.

Because peer score was so significantly devalued in this year’s methodology, it affected them less than it might have in previous years.

Some perspective on Yale’s decline, and a caveat.

On perspective: very few schools have experienced a peer score decline of 0.4 over two years. Since USNWR began the survey in its 1998 rankings, it has happened four times. (Below are the years of the survey administration, not the release in USNWR.) One was New York Law School, surveyed in 2010-2012. The other three schools were one-year drops of 0.4, St. Louis University in 2012, Illinois in 2011, and Villanova in 2011, all of which arose from admissions or prominent university scandals, as I chronicled here in 2019. Yale is just the fifth school to experience such a drop.

The caveat is, a very high peer score is harder to maintain if anything goes wrong. A few vindictive 1s from survey respondents can drop a 4.9 much more quickly than they can drop a 3.5 or a 2.0. Of course, we have no idea whether there’s simply a larger number of faculty rating Yale a 4 instead of a 5, or if other survey responses are changing the results.

It’s entirely possible that voters are “reacting” against Yale (or Harvard) for actions over the last couple of years. Whether it’s responding to public disputes arising from politically-charged episodes on campus or negative reaction to initiating the “boycott” that caused a change in methodology, some unwanted for some schools. The ~63 “boycotting” schools are clustered closer to the top of the overall rankings, and it’s possible those schools (staffed with more graduates of these schools) thought more highly of these schools—with their responses out of the rankings, the peer score fell. It’s possible that the composition of administrators or recently-tenured faculty across the country have fewer graduates of these schools than in years past, a slower shift away from institutional loyalty to their “status.” On it goes.

Nevertheless, the peer survey is the one national barometer, if you will, of sentiment among law school deans and faculty. We shall see how USNWR proceeds next year—particularly as law schools may not be inclined to share the names of potential survey respondents next fall, which means another methodological change may be coming.