How did Big Law survive the "Death of Big Law"?

The second in an occasional series I call “dire predictions.”

In 2010, Professor Larry Ribstein published a piece called The Death of Big Law in the Wisconsin Law Review. Here are a few of the more dire claims Professor Ribstein made:

“Big Law’s problems are long-term, and may have been masked until recently by a strong economy, particularly in finance and real estate. The real problem with Big Law is the non-viability of its particular model of delivering legal services.”

“When big firms try to expand without the support structure they are prone to failure. Big Law recently has been subject to many market pressures that have exposed its structural weakness. The result, not surprisingly, is that large law firms are shrinking or dying and smaller firms that do not attempt to mimic the form of Big Law are rising in their place.”

“These Big Law efforts to stay big are not, however, sustainable. Hiring more associates makes it harder for firms to provide the training and mentoring necessary to back their reputational bond.”

“In a nutshell, these firms need outside capital to survive, but lack a business model for the development of firm-specific property that would enable the firms to attract this capital. These basic problems have left Big Law vulnerable to client demands for cheaper and more sophisticated legal products, competition among various providers of legal services, and national and international regulatory competition. The result is likely to be the end of the major role large law firms have played in the delivery of legal services.”

“The death of Big Law has significant implications for legal education, the creation of law and the role of lawyers. First, a major shift in market demand for law graduates ultimately will affect the demand for and price of legal education. Big Law’s inverted pyramid, by which law firms can bill out even entry-level associate time at high hourly rates, has created a high demand and escalating pay for top law students. The pressures on Big Law discussed throughout this Article are ending this era with layoffs, deferrals, pay reductions, and merit-based pay.”

The late Professor Ribstein’s piece is only one such article in a movement of pieces that arose in the 2009-2010 reaction to the financial crisis. But large law firms appear to be thriving and continue to hire associates at ever-increasing clips among new law school graduates. Two charts to consider.

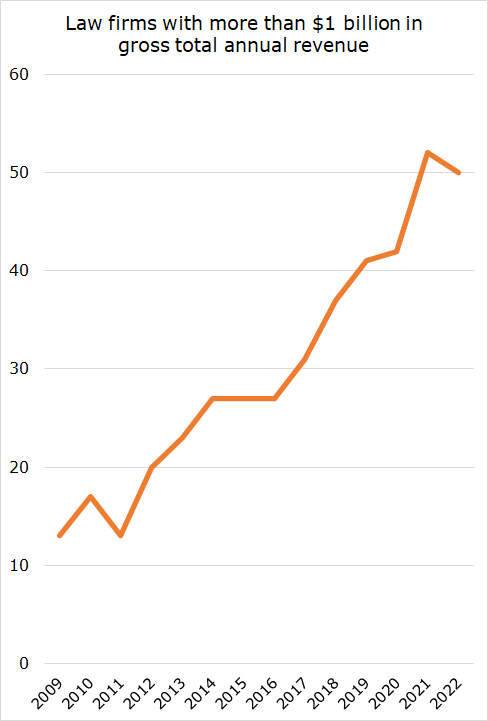

First, the number of law firms with gross total annual revenue exceeding $1 billion has climbed swiftly over the last decade or so. There were just 13 such firms in 2011, but 52 in 2021 (and down to 50 in 2022). True, inflation can account for rising total revenue. But it also reflects large law firms staying large—or becoming larger. (Figures from law.com AmLaw annual reports.)

Second, law student placement in those jobs. For the Class of 2011, nearly 4700 graduates ended up in those positions, just over 10% of the graduating class. Since then, graduating classes have shrunk by several hundred students, which has helped the overall placement rate as a percentage of graduates. But raw placement has nearly doubled in the last decade, too, to over 8500 for the Class of 2022, or nearly 25% of the graduating class.

Of course, one could find ways that “Big Law” is changing, whether that’s through the use of technology, the relationships it has with clients, its profits and salary structure, whatever it may be.

But “Big Law,” despite the dire predictions in the midst of the financial crisis, does not appear anywhere close to dead. To the extent there are large firms aggregating attorneys, with partners sharing significant profits among themselves and hiring a steady stream of associates for large and sophisticated work of large corporate clients, the model does not appear dead, but growing. Perhaps other types of disruption will appear in the future to change this model. But the financial stability of the model appears largely intact.